Debunking the Chinese property myth

11-04-2019

The argument that China’s property market is always one step away from disaster has always been a constant topic of discussion within the international investment community.

In the early 2010s, photos of “ghost towns” would make constant cameos in mainstream media, sparking fears that the slew of empty apartment blocks, vacant shops and underused white elephant projects were signals that a key component of China’s growth story was beginning to crack.

Many Chinese cities then had the dubious honour of being dubbed a “ghost town” by the media, including the likes of Changzhou, Guiyang, Huizhou and Wuxi. But perhaps the most famous of them all was the Inner Mongolian city of Ordos, which shot to global stardom when reports broke that its ambitious Kangbashi District was dramatically under populated1.

Fast forward a few years and the rhetoric had changed to a sector that was severely overheating. The skyrocketing prices were, once again, signs that a fundamental aspect of the world’s second largest economy was close to falling apart.

Or so they say.

While critics were correct to point out that both oversupply and over demand do reflect issues within the Chinese property ecosystem, using them as evidence of an impending doomsday scenario were anything but.

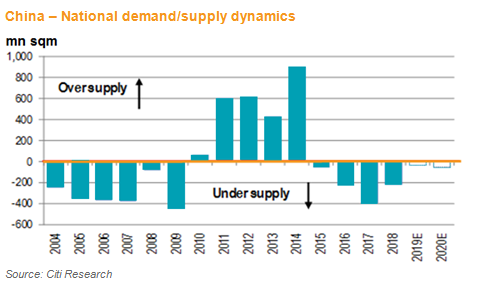

What many detractors failed to consider is that China is a very big country both geographically and economically. Demand/supply mismatches are simply unavoidable for a country as vast as China and for every Ordos, there will be a city like Shanghai, which has had to deal with pricing curbs and purchase restrictions.

From ghost towns …

There are many moving parts within the China real estate environment although a lot of the issues at play could be traced back to the country’s fixation on growth over the past decade. In order to meet their GDP-driven targets, many local governments had to turn to fixed asset investments in the form of infrastructure and housing construction.

This was how new town projects such as Ordos’ Kangbashi District came into being, which was far from an independent incident. Oversupply in many tier three or tier four cities were usually the result of an undiversified economy, an unhealthy private lending ecosystem, a disparaging population wealth gap and city planning racing well ahead of actual growth.

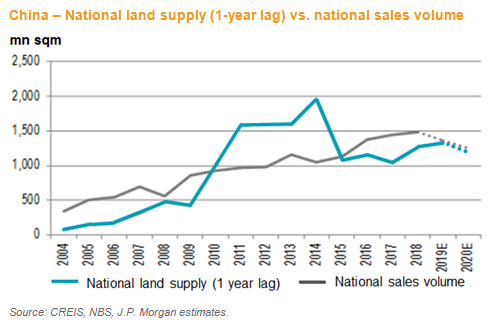

But investments were only one side of the equation and local governments also had to think of ways to fund their aggressive construction push. The simplest solution was to ramp up land supply and turn to bank borrowings that were pledged against land assets.

Doing so, however, elevated the exposure level of both banks and governments when it comes to land prices. Consequently, local governments would always be supportive of local land prices as a decline would vaporise the value of their collaterals.

… to property bubble

The aforementioned scenario was apparent across China in the early 2010s although things began to change when President Xi Jinping assumed office in 2013. China was no longer so fixated in growth and local governments were less pressured to “build to grow”.

However, the unsold inventory still needed to be cleared. And one driver occurred in 20152 when China tweaked its shanty town redevelopment programme to allow local governments to provide cash subsidies to residents of slum districts rather than in exchange of a physical unit.

This became a powerful destocking tool for the market and was crucial in relieving the oversupply pressure many cities in China were facing. Unfortunately, while supply did go down, demand continued to move in the other direction thanks to the combination of high economic growth, rising income and speculative activities.

Soon, pictures of empty cities were replaced by fears of an overheating property market especially in tier one and two cities. Former “ghost town” Zhengzhou, for example, saw its property prices surged so much that the city government had to introduce curbing measures. Many local governments also introduced similar policies, including pricing limits, purchase restrictions, stricter rules for developers to enter land auctions and tougher oversight over bank lending.

What comes now?

The majority of these cooling measures were launched in conjunction with China’s deleveraging campaign, which started in late 2016. However, rising geo-political uncertainties, slowing global economic growth and the US-China trade dispute in 2018 have added pressure on the Chinese economy and has since prompted several cities to relax certain restrictions on the property sector.

Moreover, China’s moderating economic growth will also have a big impact on shanty town redevelopment, which in 2018 made up around 15%3 of national sales. While some market participants were expecting the units of shanty town redevelopment to fall in 2019 (5.8 million units in 2018), China needs to rely on the real estate sector to support investment growth.

This is particular true when other key components such as manufacturing and exports are not performing well amidst the US-China trade impasse. From this perspective, there is a strong chance for shanty town redevelopment to be used as a “balancing figure” for China to support investment growth.

Under this scenario, the outlook is bright for many large Chinese property developers, which have taken the opportunity over the past few years to expand market share, pay down debt and focus on profitability.

We recommend focusing on real estate developers that are primarily exposed to tiers 1 and 2 cities, and have been consistently delivering strong sales growth. At an industry level, leading real estate developers have been gaining market share amid industry consolidation. Developers winning market share tend to have better research and development and land acquisition capabilities, flexibility in developing across China to zero in on areas where demand and supply are better matched, more diversified funding sources and lower cost of financing. In researching developers, it’s important to conduct fundamental research, build detailed financial models, identify sales volumes by development, benchmark sales prices with transactions in similar regions and conduct frequent site visits.

1.Source: Time Magazine, April 2010

2.Source: The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, June 2015

3.Source: Citi, January 2019

The views expressed are the views of Value Partners Hong Kong Limited only and are subject to change based on market and other conditions. The information provided does not constitute investment advice and it should not be relied on as such. All material has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable as of the date of presentation, but its accuracy is not guaranteed. This material contains certain statements that may be deemed forward-looking statements. Please note that any such statements are not guarantees of any future performance and actual results or developments may differ materially from those projected.